Through two-thirds of its elongated final season, The Walking Dead hasn't really felt like it's coming to a close. Sure, the surviving heroes have once again been facing down extinction at the hands of a seemingly insurmountable threat, but the feud between them and the Commonwealth hasn't felt any more dramatic than past conflicts with the Saviors, the Whisperers, the Governor, and so on. Now with just eight episodes to go, I've been eager to get to the part of the season that illustrates this drama as the true last act of the show. After watching the first two episodes of season 11C, I'm still left waiting for the train to feel like it's pulling into the station.

I think the issue stems from AMC's plans for a much grander Walking Dead universe--it's even marketed as the Marvel-like "TWDU." There are no less than four spinoffs either already airing or that have been announced--on top of the two that we've seen in years past, leaving the should-be questionable fates of major characters set safely aside even as their lives are supposedly threatened in these final episodes. I wrote before about how the spinoffs have deflated some of the tension in this final, important season, and though I'm enjoying the episodes in spite of that, I think the series' biggest issue goes beyond those self-inflicted spoiler wounds.

The problem with these first two episodes of Season 11C are that they don't seem to get the show any closer to saying something about its world. The show has always roped me in with its tenured characters, and I'm invested enough to never miss an episode because I want to see what becomes of them. I really do care for Daryl, Rosita, Maggie, and the rest. But character closure is, in large part, coming in the spinoffs for the series' biggest characters, so what needs to happen in these final two months of episodes--and sadly what's missing so far--is a final thesis for the series. What has living in an undead world taught these heroes and anti-heroes? After every loss, every burned-down community, every beheading of a leader, what has it all led to?

It's clear what the show would sometimes like to say--how rebuilding the world gives these survivors an opportunity to right past wrongs, how raising society from the dead gives you the chance to reimagine something better and more equitable. This is illustrated by how the Commonwealth's leadership is all too thrilled to resurrect the bygone (in their world) status quo of haves versus have-nots, of class inequality, and of political maneuvering so underhanded and backstabby that it would often make our real-world campaign ads look tame in comparison.

Much of that revolves around the ongoing drama surrounding the recently-exposed grift performed by Sebastian Milton, spoiled brat and heir to the Commonwealth's leadership role, in which he was sending the community's lower-class folks into hazardous zones to retrieve loot for his own gains, getting many of them killed and covering his tracks as often as he needed to. Disappearing dissidents, exploiting the poor for profit, and the greed and nepotism of it all are heavy-handed story branches to take, making an eye-opening thesis hard to come by. The Walking Dead isn't saying anything about those things that hasn't already been said countless times before.

While the protesters' cries outside the Milton's lavish estate are meant to drum up imagery of our real-world turmoil of the underserved seeking justice, they ultimately ring hollow with some odd writing decisions, like how the small but fiery crowd is so easily talked down by the people they're there to protest. Frankly, it all looks a little tame when you compare it to the mass protests--and downright insurrections--we've seen in real life over the last few years, and perhaps is even worse when you consider the world these people live in and how they've likely been changed by such harsh conditions before they found (or founded) the Commonwealth. After more than a decade living in such a cruel world--even if many of those occured inside the walls of safety--those left surviving in the Commonwealth are pacified too easily.

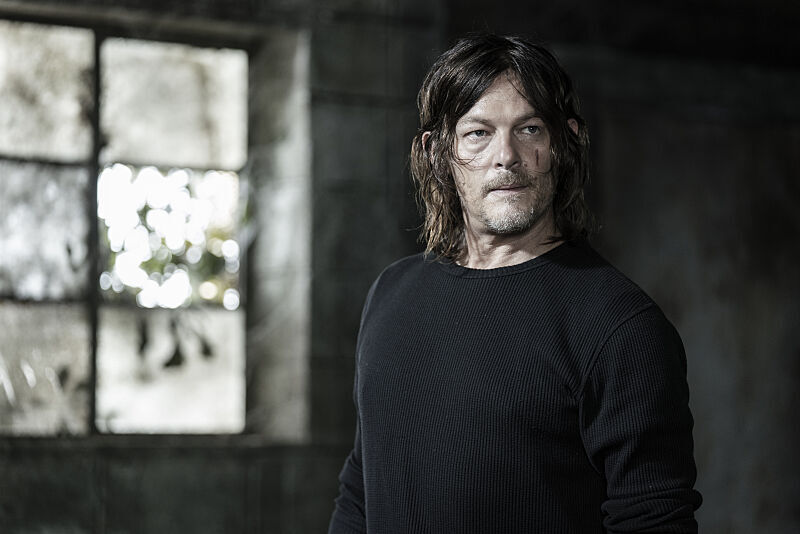

A better thread to pull on, which these episodes suggest may get yanked on more in time, regards how our central heroes are negotiating their own peaceful exit from Commonwealth even while knowing those who stay behind will continue to be subjugated by an exploitative regime. Judith takes up the voice of moral consideration in this regard, pressing Daryl to explain how he and other leaders can justify walking away to save themselves, acting like they aren't aware of the continuing strife within the Commonwealth. The two come to verbal blows--despite one being about 11-years-old--and it honestly works. It's a much less-traveled path than the cartoonishly evil Miltons and Hornsby characters. I hope we get to see more of this angle to come in the final six episodes.

These first two episodes do a good job of reminding me why I love the characters, at least, even if in one specific way, it manages to do this with a rather cheap heartstring-pull. At the beginning of both episodes--and presumably all eight in this final slate--Judith narrates an ongoing montage of the series' finer moments. Rick waking up in the hospital, Daryl finding his brother undead, Herschel's final tear-jerking scene, and more.

To the backdrop of Judith's wiser-than-her-years words and some heartfelt music, these nostalgic images hit home. By the end of the season, this will likely feel like one long fan edit of the series' best moments, and I admit, it really, really works on me. But I find it a cheap way of manufacturing intense feelings from fans, so I'm a bit conflicted each time an episode starts with these montages of melancholy. It feels like a shortcut to making me care. I'm already interested in caring, so just tell a good story.

Other times, thankfully, the present story still has the same effect of reminding why I'm still here watching when so many others have bailed. I really do care for the characters, their interpersonal dynamics, and their wellbeing. When Daryl nearly decides to kill someone in a fit of rage, he's only able to stop seeing red and be talked down when Carol intervenes. Their history together is my favorite of all, but others, such as Maggie and Negan, Rosita and Gabriel, and more are displayed to touching effect. In that way, the series does feel like it's coming to a poignant ending that I do look forward to seeing. I just wish it had a big-picture message to pass along too, and with only six hours left for me to see, it's nowhere in sight.

I love a series that makes its finale seem epic, like everything is coming to an end most dramatically. It fulfills the promise of the years one has perhaps spent prior, making the payoff incredible. I think Lost, for all its faults, does this well. Imperfect games like Mass Effect 3 do, too. There's room to be both flawed, like The Walking Dead Season 11 was always destined to be, but still memorable. Maybe it'll still get there with the final six episodes I haven't seen yet, but I'm worried these last 12 years with the show will soon come to be seen as the world's longest prequel.